“Don’t Mention The D Word”

The Forman Lecture

The Forman Lecture was a public lecture in association with the University of Manchester which offered on an (almost) annual basis between 1988 and 2007 with the aid of sponsorship from Granada Television named in honour of Sir Denis Forman, formerly chief executive of Granada Television, in recognition of his support for the highest standards of documentary film-making.

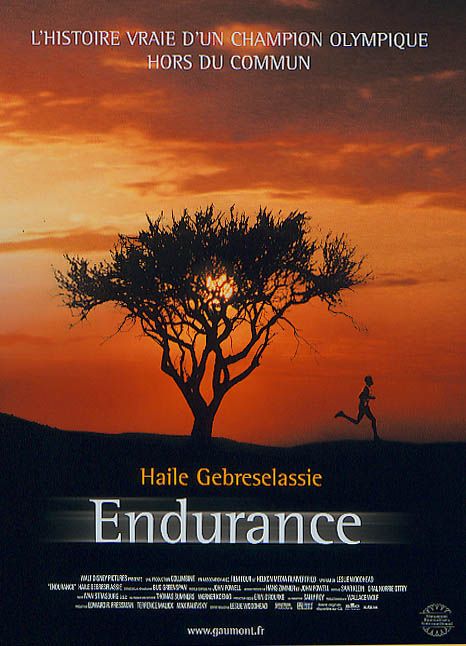

In 1999, I was invited to give the lecture and decided to speak about the making of my only feature film “Endurance“, made with the great Terence Malick Below is the full text of the lecture I gave (which can also be downloaded as a PDF here)

“Don’t Mention The D Word”

Adventures of a Documentary Maker in Hollywood

They told me never to mention the D Word. “Documentary is a no-no”, they said. The acceptable label, they suggested, the spin that was less likely to frighten off studio executives and distributors and popcorn crunchers in the audience was “Non-fiction Feature”. It was a perfect introduction to the hallucinatory project which has haunted the last 3 years of my life, the improbable business of making a documentary – I hope the D word is permissible here amongst friends – for Hollywood.

They told me never to mention the D Word. “Documentary is a no-no”, they said. The acceptable label, they suggested, the spin that was less likely to frighten off studio executives and distributors and popcorn crunchers in the audience was “Non-fiction Feature”. It was a perfect introduction to the hallucinatory project which has haunted the last 3 years of my life, the improbable business of making a documentary – I hope the D word is permissible here amongst friends – for Hollywood.

It began in early September 1995 with a phone message at home: would I call Ed Pressman films in New York? the voice said. I dimly knew something of Ed Pressman, an independent movie producer I seemed to recall, with some track record in making thoughtful and commercially successful films. To be frank, the only Pressman film I could immediately bring to mind was “Wall Street” Oliver Stone’s bravura assault on the money business, which had spawned that resonant slogan for the 1980s “Greed is Good!” But what, I asked myself, could Ed Pressman possibly want with a toiler in the British Documentary vineyard? “Could you do lunch in London?” Ed’s person asked. Of course I said “Yes”.

A week later, we sat in a noisy dining room and I struggled to try and grasp why I was there. Ed Pressman is the antidote to the stereotype of the brash Movie Producer. Small and dapper, he speaks so quietly that I was having real difficulty in hearing him over the lunchtime chatter. But slowly, some outlines began to emerge. “My friend Terrence Malick wants to do a film” Ed murmured, “about the making of a great East African Long distance runner.” OK, I got that, and I also registered Malick’s name, the legendary Hollywood Director who had made 2 haunting and widely-revered films back in the 1970s, “Badlands” and Days Of Heaven”, and had then vanished. Pressman, it became clear, had produced “Badlands”, and was keen to find a way to make what would be Terrence Malick’s first film in almost 20 years. The runner film sounded intriguing, but I still couldn’t imagine what it might have to do with me.

Ed whispered another clue. “Terry has found some of the documentaries you made in East Africa, and he admires them”. Great, how can I help? I guessed they were looking for an advisor, or a bit of local guidance to help Malick in Africa. Then Ed said: “Terry doesn’t want to direct this movie”. So – how can I help? “We’d like you to consider directing the Runner Film”. I thought I must have misheard.

Outside on the street, Pressman said he’d be in touch, but he was on his way to Australia to sort out a troubled production starring Marlon Brando. Ominously, he said he’d had to sack the director. I thought that would be the end of it, and expected to hear nothing more. 3 weeks later, I was in a London taxi when my mobile phone chirruped. It was Ed Pressman in New York. “I’ve talked to Terry,” he said, and “we’d like to commit to you to direct the film”. “You look pleased”, the cab driver said. “Good news?”

The scene shifts to Hollywood. A couple of weeks after my summons by mobile, I was in Los Angeles for a Documentary Congress, droning on to American film makers about “The British Experience” or something like that. “ While you’re in LA, you should meet Terry” Pressman said. By this time I knew a bit more about the Malick phenomenon. It was rich stuff. A sometime Rhodes scholar and MIT philosophy teacher, Malick had become Hollywood’s mysterious genius after his two remarkable films, followed by his long disappearance. He shunned all publicity, used public phones to avoid detection, gave no interviews, allowed no photographs. In the years since his last film in 1979, the stories had blossomed into myth.

I stood outside the gates of a white palace in the Hollywood hills and introduced myself to the intercom. It was another perfect day in paradise. I knew this wasn’t Malick’s mansion. He lived far away in Austin Texas, and anyway, this was hardly the style of an unworldly hermit. I gathered the palace belonged to a famous Hollywood producer, and Terry was a house guest . And here was the legend himself, tall, grizzled beard, extraordinary, unsettling eyes – a lot like an anthropologist, it occurred to me. He introduced himself in a quiet southern accent, and my relationship with Terrence Malick began.

Over the years, that relationship has been hypnotic, maddening, challenging, rewarding, frustrating, stimulating, bewildering, and a hundred other conflicting things. Within minutes, Malick was spinning metaphors to describe the way he wanted to work with me: I would be Neil Armstrong on the moon, and he would be back in Mission control; we would be Jazz musicians swapping improvisations; we would be fishermen casting our nets together. I struggled to find some firm ground amid the fog of imagery which was compounded by Malick’s hesitant, free-form sentences which never seemed to end, and to try and locate what I was getting involved with. He enthused about the Greek epic poet Pindar who celebrated the Olympic spirit, and about the nobility of Leni Riefenstahl’s “up-angle” shots of athletes in her film of the 1936 Berlin Olympics.

The closest I could get to a more focused idea of what he had in mind was his repeated references to the films of Robert Flaherty, the legendary American who pioneered the making of documentary factions for the cinema, like his 1922 film about the daily life of an Eskimo, “Nanook of the North”. It seemed we were looking for a Flaherty-style blend of observation and reconstruction to explore the making of a great runner.

Malick’s enthusiasm for Flaherty gave me pause for thought. I’d long been uneasy with some the old master’s quirky ways with reality. For an veteran factoid like me, with 10 years in the WORLD IN ACTION galleys on my record, the Flaherty approach had a whiff of swashbuckling. Getting Arran islanders to quit their motor boats and dig out their long-forgotten rowing boats to go shark hunting, sometimes at risk of their lives seemed an odd approach for a pioneer of documentary truth. The fact that Nanook was sponsored by a fur company and “Louisiana Story”, a rhapsodic film about growing up in oil country was sponsored by Standard Oil was equally unsettling. But then it was immediately clear that Malick was looking for something beyond the conventional D word territory.

I sensed from the outset that Terrence Malick was more interested in the archetype of the heroic runner, than in the specific details of an individual’s life. I’ve spent my documentary life inside an empirical British tradition which focuses on the specific and the individual, and the notion of the poetic documentary auteur jarred with my basic instincts. Even that celebrated assertion by the father of British documentary, John Grierson that documentary is “the creative treatment of actuality”, has always seemed to me precious close to a license for fiction. It was a first hint of a difference of approach which was to weave through my working relationship with Malick for the next 3 years.

Although Terry Malick had no reason to know it, alongside my films for Disappearing World, my other main television business has been with Dramatised Documentary. At Granada in the 70s and 80s we had evolved a puritanical strand of journalistic reconstructions, mainly in response to problems of access for important political stories in Eastern Europe. We called our dramatisations ‘ a journalist’s form of last resort.’ Even our austere, transcript-based recreations of a Soviet Dissident trial or a Polish dockworkers strike had provided much fodder for anguished debate about the legitimacy of mixing documentary and drama. The hybrid we seemed to be considering now, was new territory for me.

To compound my culture shock as someone who’d only ever worked with 16mm film, there was heady talk about shooting on Super 35mm film, the epic widescreen format James Cameron used for “Titanic”. And there was the music. Disappearing World had always shunned incidental music as inauthentic. Now Malick was talking about a grand score by Hans Zimmer , a star Hollywood composer who wrote the music for the cartoon blockbuster, “The Lion King”.

But between Pindar and Flaherty, and the many flattering references to Disappearing World, that first meeting seemed to to make one thing clear. “Endurance” -Malick’s suggested title – would not be any kind of recognisable Hollywood film. Indeed, he appeared obstinately determined that our film should live in an alternate universe from the Hollywood shimmering outside the vast windows. For all my grizzled British documentarian’s conscience, I was of course seduced. At the same time, though, I was startled to find myself feeling more conscious of the realities of communicating with a cinema audience than my illustrious Hollywood partner. But already, it was clear that “the D word” was taboo.

Over the next 6 months, as I got on with the rest of my life, Endurance and Terrence Malick became a constant refrain via interminable long distance phone calls and opaque faxes. Terry sent me a critical study of the poet Pindar, and said he was besieged at home in Texas by his allergy to the local Cedar trees. But to my surprise and relief he gave me total freedom to choose my own film crew and editor. Terry had agreed with me that we should keep the crew as small as possible – “Iike one of your documentaries”, he said, and I was happy to shun the spectre of a Hollywood army. I quickly recruited a team of Disappearing World veterans. It was, I confess, a shamelessly “D word” group, but Terry seemed happy.

As the months went by, it became clear that Pressman and Malick still didn’t have the money to make Endurance. I trudged round London with Ed, introducing him to possible funders at the BBC, Granada, and at Channel 4 films, who declared an interest. Then in March 1996, good news. Terry bubbled on my phone as he told me he’d sold the idea to Disney, with a budget of around 5 million dollars. It appeared Joe Roth, the head of the company was a running nut, and as Terry said, “He got it straight away”. To Joe’s reasonable enquiries about how we were actually going to make the film Terry had answered: “Trust us. It’s like asking a guerrilla army how they’re going to fight a war”. It struck me, not for the first time, that it was handy having a legend on my side.

By the spring of 1996, the Disney supremo’s question was becoming more relevant, and Endurance was becoming alarmingly real. We had to begin filming at the Atlanta Olympics in July, and nobody seemed to have much idea about how that might happen. We were in effect starting at the end. It was vital to shoot the 10,000 metres final, which we already agreed would be the climax of Endurance, and the race would point us to our hero. Pressman were busily optioning a pack of East African hopefuls, and soon had 6 world class contenders under contract.

Then things started to speed up. I went to Texas for a surreal 10 hour chat with Terry. His house remained a mirage, located somewhere over the horizon, and we talked in the restaurants and lobbies of Austin’s Four Seasons Hotel . In between baffling drives in his collapsing beige Toyota, we again encountered Pindar and Flaherty, and Terry added to the store of our working metaphors by suggesting we would be medieval stone masons building a cathedral together. He also had alarming notions about hiring African Village children to shoot some of our film, tottering presumably under the burden of our Super 35 mm Cameras. He pondered using African poetry on the soundtrack.

But we also got down to some realities. By now, we both wanted the focus of Endurance to be an astonishing young Ethiopian runner, called Haile Gebreselassie, who was smashing records all around the world. But we needed a winner, and would Haile win at Atlanta? By now Terry was also was getting involved in trying to set up his own comeback film, a 60 million dollar World War 2 Epic set in the South Pacific, and based on the novel “The Thin Red Line”. I didn’t realise however, that The Thin Red Line would invade my life as remorselessly as those American GIs slogging across the Pacific.

The Atlanta Olympics were awful. It was soakingly hot, rapaciously commercial, astonishingly disorganised. Pindar would have struggled to locate much Olympian nobility. Until hours before our race, we had no official accreditations, despite paying hundreds of thousands of dollars to the Olympic Committee, and despite the frantic interventions of a Pressman lawyer. An American Jumbo jet crashed into the Atlantic, and Airline security became stifling. Then, just when I thought it couldn’t get any worse, a bomb went off in a city centre Park. But Atlanta did have one happy outcome. Haile won the race.

The Atlanta Olympics were awful. It was soakingly hot, rapaciously commercial, astonishingly disorganised. Pindar would have struggled to locate much Olympian nobility. Until hours before our race, we had no official accreditations, despite paying hundreds of thousands of dollars to the Olympic Committee, and despite the frantic interventions of a Pressman lawyer. An American Jumbo jet crashed into the Atlantic, and Airline security became stifling. Then, just when I thought it couldn’t get any worse, a bomb went off in a city centre Park. But Atlanta did have one happy outcome. Haile won the race.

I met him just a couple of days earlier and was instantly sure he was our man. I wrote in my diary: “Lashings of charm, and a great smile”. Tiny and friendly, he talked easily in good English about his family and his passion for running. He was clearly bright and strikingly self-possessed for a 23 year old who had not so long ago left his village in rural Ethiopia to try and make it as a runner . And he said he was keen to work with us on a film. By the time he left the restaurant after finishing the glass of water which he insisted was his lunch, I was a fan. And I was desperate that he should win that race.

It was an exhausting, thrilling half hour as the runners circled the track roared on by 80,000 people, and I could hardly bear to watch as Haile slugged it out for lap after lap with a trio of world class Kenyans. As he broke clear on the final lap, I was screaming and yelling . He crossed the line utterly wasted, but he had the Gold medal in an Olympic record time. We had our hero. There was joy in LA, where Terry and Ed were hosting an Olympics party, having wisely passed up the chance of a trip to Atlanta. Now we had the climax , but we hadn’t even begun to begun to sort out how we were going to make the rest of the film.

The next few weeks were a blur of preparation . I flew straight from Atlanta to Los Angeles to meet Terry in yet another borrowed dream Palace, this time in Malibu but modelled on the Alhambra, with Bob Dylan as next door neighbour. He was thrilled with the Olympic footage and with the choice of Haile, and he was euphorically supportive: “Don’t worry about Disney” he said. I’d wrestled for months with notions of how to approach the film, and decided that I felt more comfortable with something that was largely observational, relying on scenes of peasant and city life which somehow echoed Haile’s experience. To my relief, Malick agreed, saying he felt Endurance should favour observation rather than reconstruction. And he boldly supported subtitles.

Within days I was on my way to Ethiopia for a frantic week of meeting Haile and setting up for 3 months of filming. It was weird for me being back in Addis Ababa which I’d passed through 4 times on my way to the Mursi. Now, I noticed, the Mursi were featured in a tourist brochure. I was more glad than ever that Haile had won that race, since it was taking me to a country where I had at least some idea of how to function. Most crucial of all, I had Mohammed Idris .

Mohammed is a remarkable man, formerly an official with the wonderfully named “Ministry of Information and National Guidance”, who had been with me on three of the Mursi expeditions. He had been assigned to watch over us in the 1980s as a government minder, and always looked even more out of place than the rest of us in his immaculate pressed slacks amid the muddy discomforts of the Lower Omo Valley. But I had quickly come to like and admire Mohammed. He was a consummate survivor, a devout Muslim working in a Communist bureaucracy, but he was also a film maker with a consuming interest in what we were doing, and an unstoppable talent for solving our film-makers’ problems. He was my first port of call for surviving the upcoming storm of Endurance. David Wason joined us from Granada, another Disappearing World recruit. Between them, Mohammed and David set about tackling official Ethiopia.

Meanwhile, I spent days with Haile, recording a detailed account of his life, and his struggle to be a runner. He was a terrific witness, full of vivid memories and surprising anecdotes. He told us how it had been for him, growing up with his 9 brothers and sisters in a one room mud Tukul , the son of a tough peasant farmer. He told us about running barefoot to school through the bush, 6 miles every day, about stealing his father’s radio to hear his childhood hero Miruts Yifter win a Gold Medal at the Moscow Olympics in 1980 and how it had changed his life. He told us about his struggles with his father’s hostility to a life wasted on running, and his tussles with Ethiopia’s Athletics bureaucrats. He told us how his beloved mother had died when he was only 10, and it was apparent that he was still devastated. As he talked, I could sense the film taking shape.

With Haile’s brother Zergau, we had a whirlwind 36 hour experience of that other world where Haile had grown up. For the first time, we rattled down the hair-raising road from Addis to Asela, a 4 hour ordeal of near death experiences which was to haunt our nightmares during the filming, gaining the label “The Road of Dead dogs”. But at the end of the journey was a god-given location. Not even Disney’s top Production designer could have improved on Asela. 7000 feet up, overlooking the stupendous Rift Valley, on that first afternoon, the countryside looked like a cross between Tuscany and Provence.

We met Haile’s father, still handsome and formidable at 73, and still herding his cattle. Zergau showed us the great tree, 200 years old now, where the kids used to play. And we got our first taste of the Asela Ras hotel, the very basic guest house which would be our crew accommodation for weeks of filming. The blood -coloured water which stuttered out of the taps was not a happy omen.

We also went house hunting. Our primary location would inevitably be that compound where Haile grew up, but the real thing had collapsed in a storm 20 years before. Less than half a mile away, we found a bustling compound with its Tukul and animals and pretty children. We talked to the farmer, a canny-looking chap in a green baseball cap, and felt out the possibilities. He looked like he’d drive a hard bargain.

My location producer Sally Roy looked troubled. Sally was another of my D word recruits, a young American I had worked with on a number of documentaries, and who I’d come to value for her breezy ability to solve the insoluble. If Sally was troubled now, I was troubled. How, she asked, could we possibly reconcile the insane demands of a film location with a hard-working farm? She had a suggestion. Since we want to share something of the daily realities of the farm , without colliding with the ongoing lives of the people, why she asked, don’t we build our own Tukul near the compound?

It was a defining moment. This was it, I thought: Hollywood meets Disappearing World. I felt a pang of discomfort, but after a moment’s thought, I knew Sally was right. It was clear already that this couldn’t be a purely observational film. We had to tell the story of Haile’s boyhood, and that meant re-enactment. I had to work out a third way – to coin a phrase- between observation and staged drama. We would have somehow to find a form which could allow us to employ reconstruction, with actors perhaps, while maintaining the freedom to record the daily lives of the people around us.

I was struggling to find a form which would allow me to explore the central issue of Endurance – what were the special ingredients in that world which shaped Haile Gebreselassie and allowed him to become a great runner. I was aware that it was an issue closer to Disappearing World than to Hollywood, but somehow I had to find a meeting place. Meanwhile, we needed a Tukul. Flaherty had reconstructed Nanook’s igloo, so we had a distinguished precedent. We commissioned the canny farmer and Haile’s brother Zergau to build us a Tukul just like the one the Gebreselassie family had been raised in. I thought it was better not to tell Terry…

In Addis, I grappled with the problem of how to reconstruct Haile’s boyhood. Who would “play” him, his mother, and his father? I was sure by now that trained professional actors, whether based in America or Africa, wouldn’t be right. I would need people who could milk a cow with conviction, and live the lives of Ethiopian peasants without artifice. We had met some village boys in Asela, but none of them seemed right. Then I met Haile’s nephew Jonas, a bright and charming 10 year old, and Haile’s oldest sister Shawannes, quiet and impressive, with a wonderful face – “just like my mother”, Haile said. I wondered what Hollywood would make of them as stars. I tiptoed round the idea, and headed back home to get ready for liftoff, now only weeks away.

My priority now was to try and agree a narrative outline for Endurance with Terrence Malick. Armed with Haile’s stories and what we’d seen on the recce, I wrote a 16 page outline, a scene by scene scenario for the film, following our hero’s life from boyhood, through the death of his mother, to struggles in Addis and gathering international success, climaxing at the Olympics. Terry’s response was instructive. He wanted to lose the “gathering international success”, -”that’s just journalism” he said – and cut directly from the poor boy in the big city to the Olympics. I could see the dramatic force of that, but it was more evidence that Malick was more interested in the Archetype than in the individual. In fact he was never to meet Haile, or even to speak to him on the phone. But Terry was as disarming as ever. “Of course I may be entirely wrong about all this” he concluded, “ and I have more to learn from you than to teach”. He thought it was best not to show my scenario to Disney – “best to avoid getting committed to anything” he said.

2 days before we were due to leave for Ethiopia, I met Terry in London. He was at his most rhapsodic: we should “seek the glimmer of gold in the stream”; we should consider using Ethiopian poetry on the soundtrack; we should “not be confined by the linear facts of Haile’s life”. He quoted Mother Teresa on “material poverty and spiritual wealth”. He fretted about our “abbreviated filming schedule” – at two and a half months, twice as long as anything I’d ever known in British Television. “After we’ve had such problems putting to sea, “Terry said, “ we should allow ourselves time to cast the net wide”.

That luxury of time seems to me one of the key elements of good documentary which has often been lost in today’s hyperactive television environment. I recall some Disappearing Worlds used to shoot for as long as 12 weeks in the 1970s in those dreamy years before the tyrannies of total costing. It’s hard, I think, for really worthwhile documentary to happen when an accountancy-driven schedule forces instant judgements and weary compromises. It’s all too easy to understand how the shorthand of docusoaps can be an obvious answer, or more alarmingly how a panicked director might resort to giving truth a nudge to get finished on time.

Endurance might have a multitude of problems to face, but time clearly wasn’t going to be one of them. Terry Malick and I embraced, and said our goodbyes . Just over a year since my first meeting with Ed Pressman, it was time to go and make a film.

There were just 6 of us in the crew setting out for Ethiopia, but our 106 pieces of baggage completely swamped the check-in area at Heathrow. With a quarter of a million feet of film and 2 bulky Super 35mm Cameras plus all their bits, it was hardly surprising, but it was also an early warning of logistical horrors to come.

As we settled into our base hotel in Addis, it was apparent that Hollywood was ahead of us. We got a copy of an amazing Fax from Joe Roth, the head of Disney to the President of Ethiopia, written on Mickey Mouse-headed stationery. Joe wished to share his “excitement and vision” about Endurance. The Disney insurers,it seemed, had a less elevated concern: they needed an urgent Urine sample from Haile to reassure them about the fitness of one of the fittest men on earth. Disney’s lawyers were also fretting that we should get signed release forms from everyone we filmed, particularly, they said people filmed in sensitive circumstances such as “sex or elimination”. Struggling through the teeming, chaotic Mercato, the biggest market place in Africa looking for materials to build shelves in our crew bus, it was hard to take Tinseltown’s concerns seriously.

We began filming at last with a 5am dash through the darkened city streets of Addis Ababa to shoot Haile’s regular morning run. I feared for my life as Haile hurtled past goats and sleeping people in his new Mercedes, to the accompaniment of his favourite Hip Hop cassette on the car stereo. I thought of Terry Malick’s noble archetypes, and the poet Pindar. But as we took our first halting steps up the Everest of Endurance, trying to keep up with Haile’s effortless run across the Ethiopian landscape, I got my first lesson in the challenges to come. Even with the vital assistance of two local film crew who had joined our team, the camera was dauntingly heavy, and every lens change was a slow business. And even out here beyond the city limits, Haile was a big star, attracting groups of admiring locals. It was going to be hard to capture those images of the unknown country boy in the big city.

From the start, though, Haile was a joy. Intensely curious about everything we were doing, full of suggestions about how it might be done better, he was ready for anything. We also became immediately aware that he had the tearaway attention span appropriate to the world’s leading runner, but was less well adapted to the slow motion business of film making.

But our greatest concern in those early days was just learning how to operate, lugging ourselves and our piles of equipment between Addis and Asela down the Road of Dead dogs. We removed the seats from a bus, and built shelves to hold our gear, cushioned against the rough and tumble of the pot-holed roads by piles of mattresses. Even with 3 additional vehicles, we were still cramped.

Still, some basic issues did begin to resolve. Mohammed led us proudly to our key location, the specially-built Tukul he had been supervising for weeks. It looked splendid, blending into the compound as though it had been there for years. Cameraman Ivan Strasburg immediately began organising openings in the walls so that he could reflect sunlight into the dim interior.With no electricity, we planned to film without lights, relying on natural daylight and Ivan’s ingenuity. Hollywood was, after all, 8 thousand miles away. Sally reported however, that Disney was asking for a list of our production staff: Makeup, Wardrobe, Set designers etc. The mutual incomprehensions of Burbank and Asela were already unbridgeable. It seemed wiser not to try, so we sent the Disney lawyers instead another huge batch of release forms, dutifully gathered from everyone we’d filmed and mostly signed with thumb prints. Terry Malick was being endlessly supportive on his regular phone calls. I wondered how he’d feel when we shipped our first rushes after 2 weeks.

As we began to accumulate observational material of life in the countryside and in the capital, I had still not reached final conclusions about who our “actors” should be. We met more boys in Asela, but none seemed right; Haile’s uncle Tadessa looked startlingly like his father, and he agreed to play the early father’s role alongside the boyhood Haile. We were also experimenting with strategies to film in Addis without attracting the attention of its 4 million residents. Blacking out the windows of a van , and shooting through a part-opened door seemed promising, but it was a gruelling way to garner a few pictures. Even after 2 weeks in Ethiopia, I felt we’d barely dipped our toes in the water.

From the very beginning of Endurance, I’d been apprehensive about the whole business of reconstructing Haile’s early life. It wasn’t that I had moral qualms about the requirement for re-enactment in this film. There was after all no question that any audience could be confused about the status of our reconstructions. For our Granada Dramatised Documentaries, we had always been fastidious about labelling the films at the outset, spelling out for the audience the nature of the dramatisation they were about to watch, and the status of the research which underpinned it. I recall that one of my dramadocs in the 70s had an interminable 11 minute explanatory prologue – imagine trying to inflict that on an audience in the 1990s.

But it was obvious that Endurance didn’t involve the journalistic issues which had rightly concerned us in making a film of record about the Soviet invasion of Czecholslvakia. Our reconstructions would unambiguously be dramatisations rather than straight documentary. My concern now was more practical – how to operate with a non-professional cast in a foreign language, and whether my real life actors would feel able to act.

Finally it was time to give it a go. We began with a scene where Haile arrives in Addis for the first time as a wide-eyed teenager, and goes to stay with his older brother. We located the actual house and got permission to film from the bewildered owner, and we recruited Haile and his brother to recreate the scene of the arrival. I’d concluded that any dialogue in the film would have to be in Amharic, subtitled where necessary. We had, of course no script, and at this point Mohammed Idris became absolutely vital. I talked to Mohammed about the scene, and he asked the brothers to improvise the sort of things they said to one another at the time. He monitored the dialogue, and told me what had been said. It was improbably cumbersome, but it seemed to work. I had to leave it to Terry to explain to Disney what the heck was going on. Haile and his brother were impressively natural, even over several takes and changes of angle, and the working method I evolved with Mohammed that morning became the model for the rest of the filming.

It also resolved my uncertainty about who to cast for the other roles, especially the boyhood Haile and his mother. The gain in involvement and understanding we would make by asking Haile’s own family to represent his story was now obvious. We asked Haile’s nephew Jonas and his oldest sister Shawannes to be boy and mother. I had my cast.

We crouched in our blacked out van to shoot Haile as an unknown walking the city streets, disguising him in my bush hat and sunglasses until the last possible moment. It was bit like trying to film incognito with Paul McCartney in Carnaby Street in 1965, but we got our film before Haile was swamped by admirers. It was more “Van on the Wall” than “Fly on the Wall”, but at last we were learning how to work.

It was almost a month before I had Terry Malick’s first reaction to what we were filming. We were shipping rushes to New York for processing every week, but by the time they survived the vagaries of customs in Ethiopia and America and then Video copies reached Terry in LA, it was like sending a message to a distant star. Sally had made sure we got our copies first, so I could know what we were talking about. I’d been pleased by the first batch of rushes, tentative and explorative early material which already seemed like something from a former life, but I had no idea what Terry might make of them “Firm salutations to all concerned” was his message from Mission control.

It was a big relief, but of course there were surprises wrapped up with the salutations. His greatest enthusiasm was focused in what seemed to me the oddest places: a scene we’d filmed at a Holy Water shrine outside Addis where sick people sought help in a communal shower from a priest in a yellow Mac thrilled Terry; baboons scavenging on a rubbish dump also excited him. He had a couple of concerns about Haile: his tracksuits looked too smart, and perhaps he was smiling too much. But he was hearteningly supportive, and said Ed Pressman shared his good feelings. He told me he wasn’t letting Disney see anything – very wise, I thought, and much appreciated by all of us far from Burbank. It was a crucial insulation from Hollywood scrutinies which Terry Malick managed to maintain not only through the shooting, but even during a year of editing. God knows how he managed it, but I suppose it’s one of the bonuses of being sponsored by a legend.

By now, we were getting into the heart of the film. Looking back , I’m alarmed to realise how far into filming we’d gone before I really knew what I was doing, and had evolved with the crew a way to make this strange hybrid. Again, it occurred to me how impossible it would have been to make this film under the time constraints of a tightly- scheduled Television documentary.

It was harvest time in Asela, which turned the landscape into ravishing perspectives of yellow and gold – a banquet of images for greedy film folk. We asked our family actors to join in with a real harvest, and as Jonas tore around the fields as a boyhood Haile, yelled at by his “actor” father, the line between observation and reconstruction seemed to blur in a way that felt to be working. There were moments when I found myself genuinely confused about the layers of reality – who was who and when was when? But at least the farmer seemed to be happy to have the help with his harvest. Then we asked our family to join in with a mass christening for 5 babies which was happening in the Coptic Church on a hillside above Asela, and observed what happened just as I would have done for Disappearing World.

Sometimes, Mohammed Idris worked with local people to organise traditional activities. He invited a group of local priests and wise women to anoint the great tree close to our Tukul, and again we involved the family and filmed what happened. Mohammed’s most extraordinary contribution, however, was the funeral. We needed to reconstruct our pivotal scene the moment which would mark Haile’s transition from boyhood to the second act of the film where he would play himself as a young man. He had made us understand the life-changing significance for him of his mother’s early death, and I wanted to record the power of a traditional funeral.

On the appointed day, we arrived at the Tukul, unsure what to expect. I was aware that Mohammed had been particularly busy in the previous days arranging the funeral, but none of us had anticipated the extraordinary scenes which unfolded that morning. Two hundred mourners arrived, along with a dozen gorgeously robed Coptic priests, and then we were simply swept along for the next 3 hours, trying to follow the irresistible tide of emotion and spectacle which swept us from the Tukul up to the Church on the hillside. Haile’s nephew Jonas sobbed inconsolably, the mourners sang and wept, and it was impossible to believe there was no body in the simple coffin. When it was finally over, we were all exhausted by the power of the occasion. I was also bewildered. How on earth had these people managed to discover so much emotion in these strange circumstances? It wasn’t the first time I’d been startled by the genuineness of our peasant actors, and I’d come to understand that for people unfamiliar with second-hand emotion via TV or Movies, the realities of feeling were not filtered through imitation. Jonas told me he’d had his own way of finding tears at the funeral: “I thought about my aunt who died not long ago” he said. It was a technique which would have struck a chord with many a method actor in Hollywood.

As we finished our second month in Ethiopia, we all began to feel we’d lived here most of our lives. Terry Malick called from LA every week, ever-supportive, ever enthusiastic about the rushes he was seeing. I was becoming aware, however, that he had an underlying concern: was it all looking too beautiful? It struck me this was perhaps an odd concern for a man who had made two of the most beautiful films in Hollywood history, and it was an unexpected comment for a Disney film.

But we recognised what Terry might be fretting about. I confided to my diary: “The sub text is a concern about the beauty of this place = lack of struggle = no storyline. We all share an understanding about the ambiguities of shooting a cinema film in such a place which may confirm Rosseauesque stereotypes of noble savagery, instead of capturing the toughness of life hereabouts. Odd to be instructed about this from the comforts of LA , but we’re all well aware of the pitfalls of backlit glamour. The dilemma remains how to make a Hollywood movie without losing the tough realities of life in a Tukul complete with flies and cowshit. How strange that we should find ourselves cast on the Hollywood horn of this dilemma by Hollywood itself.” I tried to reassure my co-pilot that there was plenty of tough, fly-blown material in the stuff he hadn’t yet seen, but it was hard to convey the reality that a gorgeous landscape did not mean an easy life. “I never realised it was beautiful when I grew up here” Haile told me. “It was just where I lived”.

The routines of dividing our lives between Addis and Asela began to weary us all. But there were still some surprises. We got arrested for a few hours by Haile’s Athletics bosses, desperate for a share of our budget. Via a helicopter piloted by a born-again missionary, we got some stupendous pictures of Haile running along the edge of the Rift Valley. Terry vetoed every frame: “Too Hollywood” he said.

The terrible hotel pianist was playing “Jingle Bells” when we got back to Addis after our final trip up the Road of dead Dogs – 2 dogs, I donkey, 3 wrecked cars was our farewell tally. It was December 15th. I braced myself as usual with a stiff Gin & Tonic for the call with Terry. To my disbelief, he began at once urging our immediate return to Ethiopia after Christmas. He was now weeks behind in viewing what we’d shot, at least 100 rolls unseen, but he felt sure we needed more. I refused point blank. Until he’d seen the material and viewed my first edit, due at the end of March, I couldn’t see any point in floundering through yet more film without knowing what we were looking for. He took the point, with reluctance. I didn’t dare to tell him we were going home the next day. We got stranded overnight in Asmara with a broken plane, but we did make it home for Christmas. Terry called me on Christmas Eve and insisted I avoid thinking about Endurance until the New Year. We traded verbal hugs.

1997 began with a call from Terrence Malick. He still hadn’t seen all we’d shot, but wanted to discuss our return to Ethiopia, and he was looking forward to “swapping riffs” during the edit. “You’ve done a great job”, he said. “you have a terrific film. We just want to allow you to make a masterpiece”. It seemed we were going back.

I phoned Hans Zimmer in Los Angeles to try and get some musical sketches from him for my edit. He was charming, but vastly busy scoring Hollywood epics. I quickly concluded that the real work on the music for Endurance would be done by a young associate of Zimmer’s, an Englishman called John Powell. He was due to be in London as I started my edit, which was good news.

During our next phone marathon, Terry told me that he was now definitely going to make his own film, his first since 1979. “The Thin Red Line” would be shot mainly in Australia, filming for 128 days, beginning in the summer. He was off in a few days for a major recce, so I’d be starting my edit without my “co pilot”, as he now dubbed himself. In fact I’d agreed with him from the outset that I would have 7 weeks to work on my own first cut before showing him anything, but I wondered how the fact of ‘Thin Red Line” would now affect the progress of “Endurance”.

Working with my longstanding Editor and friend Oral Ottey on trying to shape Endurance was a joy. John Powell’s first stab at some music was thrilling, an emotional fusion of music we’d brought back from Ethiopia with Western harmonies that sometimes reminded me of Aaron Copeland. At Terry’s instigation, we included some of the interview I’d done with Haile, which he felt was “honest, lovable and noble”. Oral agreed with me, however, that the 19 pieces of African poetry Terry had sent over, didn’t seem to do much for us. We dumped the lot, and decided to fight that battle later. We also felt that Endurance needed a narration to underscore and personalise the story, in the form of an ongoing voice over by Haile. It was, after all, a device Terrence Malick had used to memorable effect both for Badlands and Days Of Heaven. By mid March, we had a first cut of 117 minutes, much too long we knew. It was time to show it to Terry, now returned from his Australian recce.

We arrived in an LA gripped by Oscar fever, the local TV news featuring an item on “Jewels the stars will hire”. Our destination was less glittering, a brick box of a building in Santa Monica which is Hans Zimmer’s base, and the facility Terry had chosen for the next stage of the edit. We stuck our tape in the player, and hoped for the best. To my dismay, Terry scribbled ceaselessly on a notepad throughout the screening, barely looking at the screen as far as I could see. When it was over he said: “We will have a great film”, and asked to see it again. When they came, his comments were gracious, positive, and I thought mostly wise. He wanted less voice over, and less music, he wanted a clearer story line. We felt good.

The priority now, Terry felt, had shifted from observation to reconstruction. He wanted to fill out the relationships between Haile and his parents, to put more effort into exploring the tensions between Haile and his father about the boy’s ambition to become a runner. “Endurance won’t work in the cinema if it’s just reportage”, Terry said, “ we need to move into a different gear”.

I could see the wisdom in that. I realised that, after all the debates and all the confusions, I was, in the end, making some kind of Robert Flaherty film. That didn’t, by now, trouble me. I felt that, having struggled to evolve a way of making the film, this was the right way to go. And Haile’s family would ensure that we didn’t distort the emotional realities of their lives. But I was concerned that Malick’s desire for more emotional exploration would stretch my peasant ‘actors’ to the limit. Meanwhile, Terry would work with Oral for the month I was in Ethiopia, trying out some ideas of his own – mainly, it seemed trying to thread the Olympic race through the film. Oral and I both had our doubts, but we would see.

It was a hard month in Ethiopia. Haile was in strict training now, and less available for the demands of filming, the family began to weary of our requirements, some of the crew were unwell. The ravishing autumn perspectives of Asela had turned to spring mud, and it was virtually impossible to match our reshoots. Then 2 terrorist bombs went off in restaurants we regularly visited. But through it all, we were getting some valuable stuff, and again I was impressed by the conviction with which our “actors” could replay the most emotional scenes from their own lives. Haile’s real father, now playing himself for the scenes with his adult son was extraordinary as he struggled to convince Haile to forget his running ambitions. As he lobbied his son to give up running and be a lawyer or a teacher, I wondered how he could still recover the force of his hostility now that Haile was an Olympic Gold Medal winner with 2 Mercedes.

By the time I got back to the editing room in Los Angeles, Terry had left for the South Pacific to begin shooting The Thin Red Line. The version of Endurance he had left behind with Oral was leaner, but it preserved most of what I cared about and I thought it worked well – except for the race being woven through the film. Oral reported that he hadn’t in fact seen much of Terry who was hugely overloaded with his upcoming film, but he had some cherishable stories about the Malick myth. A Hollywood hopeful had asked Oral if he could come into the great man’s cutting room, and when advised that Malick had already gone to Australia replied: “You don’t understand. I just want to stand where he has been!”

For the next month, Oral and I worked in the brick box, tightening and shaping Endurance. We sent cassettes to Terry on the Great Barrier reef, and persuaded him that the race worked best as a climax rather than a trudge through the film. We felt we could have a locked picture by early June.

Then Ed Pressman dropped a bombshell. He rang me to say that Terry really didn’t want to sign off on Endurance while he was on the other side of the world. “It’s Terry’s original vision, and I have to respect that” Ed said, though I could detect that this was painful for his long-suffering budget. “We’ll have to go on hiatus” Ed told me, rather quaintly, I thought, ”until Terry returns in December”. And that was that. For the next 6 months, Endurance was frozen.

I went to China and Iran to shoot a couple of documentaries for Television. It was bliss to just go and do it, without the need to check in with Mission control. Then, defying all my doubts, Terry returned with Thin Red Line duly completed, on time and on budget. By now, though, I had lost my editor and my best ally. Oral had gone off to cut a feature film, and a new editor, a young American had been hired to complete Endurance. By the time I got to LA in January 1998, a lot had happened.

The Endurance edit had now shifted to Warner Hollywood, a real studio lot this time, decorated with memories of Sam Goldwyn and Frank Sinatra. Terry was editing Thin Red Line there, so he’d moved the Endurance edit onto his territory. I pulled into the lot and found my parking space had my name on it, which was fun. I found Endurance was now a good deal shorter, just 83 minutes, all the voice-over had gone, to be replaced by a dozen austere caption cards in mimicry of Flaherty. Terry had cut some of Ivan’s most ravishing shots, dismissing them as “cornflakes”. He showed me some of his rushes – astonishing I thought, but it also seemed to me that Terry’s own cornflake count was remarkably high. Endurance now had a brief prologue, where Haile spoke about his life and his beliefs. There was, if anything, even more of John Powell’s marvellous music, which I was happy about.

Oddly enough though, not a single new sequence or shot had been excavated from the rushes, and the film was still shaped much as I’d left it. I felt, with some surprise, that I still had my film. It was, it seemed to me less Hollywood than ever. Malick’s adjustments intrigued me, and suggested new ways with “the creative treatment of actuality”. Terry had given the film a more dreamlike quality, what he called “an alpha rhythm through the movie”, making it , he felt, more like a poem than a film.

I worked with the new editor for a few days, shifting some things back to the way I’d had them. Terry wandered across every day from his own edit, and shifted some things back again. “What do we do if we fail to agree on some things in the end?” I asked him. “That won’t happen”, he said. We screened the film for the first time for a few people in a little theatre on Sunset Boulevard. They seemed to love it, and Martin Sheen told me he cried – “more than once”…

Of course it wasn’t over yet. I returned to LA in April last year to get involved with the sound design and music. ENDURANCE had a new recruit, a charming French sound designer called Claude, who confessed himself “Scotche sur le plafond” by the film – I guessed this meant “sellotaped to the ceiling”. He said he’d named his cat Terry because he’d loved Badlands so much. Witnessing Claude’s tireless efforts to explore what he called “different flavours” of African cricket sounds, and his experiments with an Australian bull roarer to express the mood of Haile’s great tree was a glimpse of the dizzying excesses of a Hollywood soundtrack. Claude also replaced Haile’s every footstep with specially recorded steps produced by a 70 year old Hollywood footstep virtuoso. We were a long way from observational documentary film making, but the track was sounding extraordinary.

John Powell’s music continued to thrill me. He got some Los Angeles-based Ethiopian musicians into the studio, and blended their sounds with the tracks we’d recorded in Ethiopia and material he’d recorded with the London symphony orchestra. By now, we had almost 100 separate soundtracks, and our final sound mix was booked to take place in a major Hollywood dubbing theatre in 2 days time. After a series of 18 hour days on the soundtrack, Terry Malick came to listen. “If only we had 2 more months”, he mused, “this would be a great film”. I knew then I wouldn’t see ENDURANCE finished on this trip. I went home with Terry’s final message to me : “Preserve the simplicity of your Mursi films. I’d rather have this film authentic than successful.”

3 weeks later, I was back in LA. The valet parking team at the hotel greeted me like a familiar friend. This time we were really going to finish the film, Terry said. And his key note for the sound mix, he told me was “We don’t want to feel the hand of the artist.” I gathered he was concerned that Claude’s huge multi-layered soundtrack might overwhelm the film. “Very French” , Terry thought. I thought Terry could be right.

We’d got access once again to the Hollywood feature film soundstage, on condition that we worked after the big budgets had gone home. For 10 interminable nights we slogged through the film, trying to find the right blend of those 100 plus sound and music tracks. Terry called by every night for an hour, and added his diffident suggestions to the collective agonising. Claude’s sound symphony was massively impressive, but we drowned in options, and the challenge of excavating a single footstep from the uproar at 3am began to exhaust us all. I looked around one night and found 5 of my team deeply asleep. I couldn’t blame them. ENDURANCE had never seemed a more appropriate title.

On the last evening, we gathered to view the whole film. It would be the very first time we had the chance see it for real – on a huge sceen with the full stereo surround-sound track. After 3 years with ENDURANCE, I didn’t really know what I’d feel.

Well what I mostly felt was a vast, weary relief that it was done. I was aware as well that it wasn’t like anything I’d done before, or anything I could remember having seen. The layers of observation, reconstruction, archive film, sports documentary, of ethnography and drama were so tangled that I’d long ago abandoned any attempt to categorise the film. It tested and re-defined some of my long established ideas about documentary and about representing reality.

It has been an absolutely fascinating and rewarding thing to do, an intriguing universe to visit, but not perhaps where I’d choose to live full time. I have learned a lot, but I’m still an unreformed documentary man, and I still believe in the old virtues of trying to get it right, and preserving the contract of trust with the audience. And Hollywood didn’t need to worry. Endurance could never be mistaken for one of those D word things.